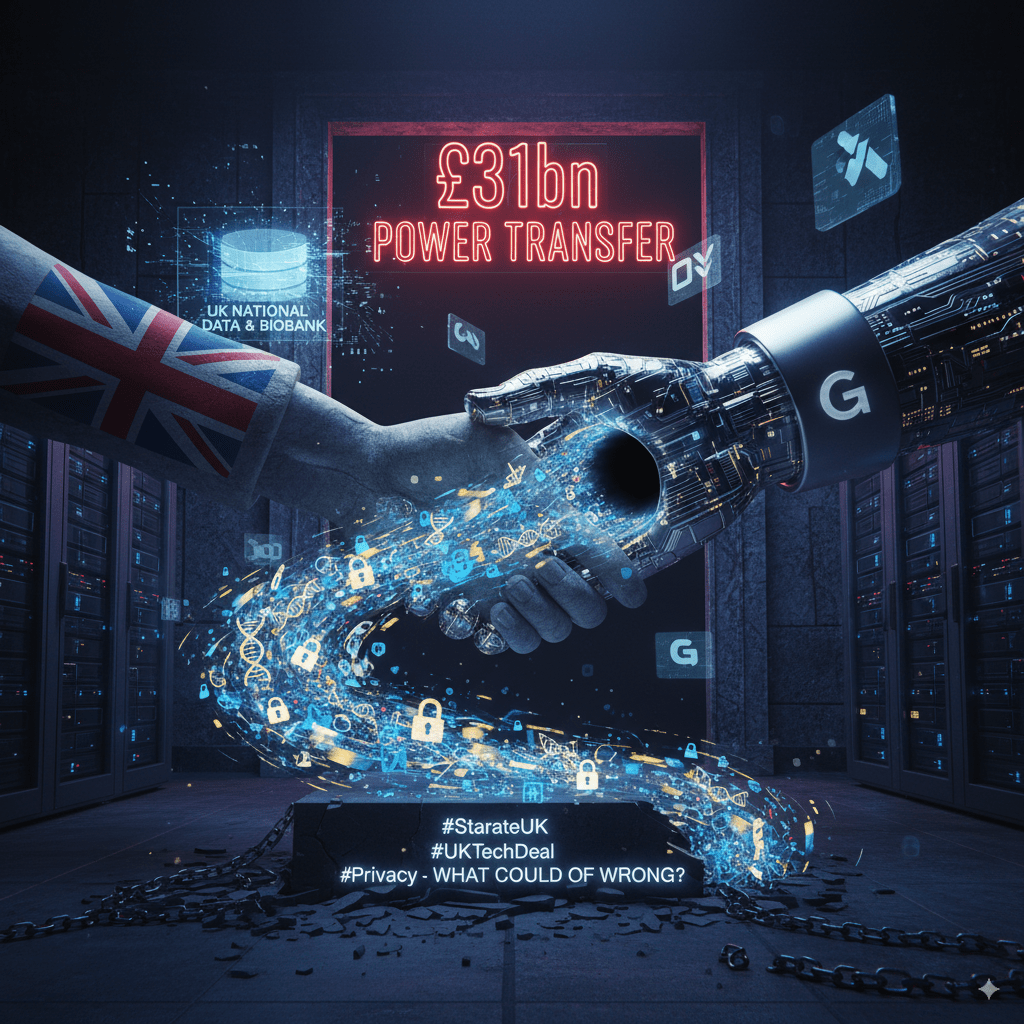

Whilst all eyes are on Trump at Windsor the UK Government announced the “Tech Prosperity Deal,” a picture is emerging not of a partnership, but of a wholesale outsourcing of Britain’s digital future to a handful of American tech behemoths. The government’s announcement, dripping with talk of a “golden age” and “generational step change,” paints a utopian vision of jobs and innovation. But peel back the layers of PR, and the £31 billion deal begins to look less like an investment in Britain and more like a leveraged buyout of its critical infrastructure.

At the heart of this cosy relationship lies a bespoke new framework: the “AI Growth Zone.” The first of its kind, established in the North East, is the blueprint for this new model of governance. It isn’t just a tax break; it’s a red-carpet-lined, red-tape-free corridor designed explicitly for the benefit of companies like Microsoft, NVIDIA, and OpenAI. The government’s role has shifted from regulation to facilitation, promising to “clear the path” by offering streamlined planning and, crucially, priority access to the national power grid—a resource already under strain.

While ministers celebrate the headline figure of £31 billion in private capital, the true cost to the public is being quietly written off in the footnotes. This isn’t free money. The British public is footing the bill indirectly through a cascade of financial incentives baked into the UK’s Freeport and Investment Zone strategy. These “special tax sites” offer corporations up to 100% relief on business rates for five years, exemptions from Stamp Duty, and massive allowances on capital investment. For every pound of tax relief handed to Microsoft for its £22 billion supercomputer or Blackstone for its £10 billion data centre campus, that is a pound less for schools, hospitals, and public services.

Conspicuously absent from this grand bargain is any meaningful protection for the very people whose data will fuel this new digital economy. The deafening silence from Downing Street on the need for a Citizens’ Bill of Digital Rights is telling. Such a bill would enshrine fundamental protections: the right to own and control one’s personal data, the right to transparency in algorithmic decision-making, and the right to privacy from pervasive state and corporate surveillance. Instead, the British public is left to navigate this new era with a patchwork of outdated data protection laws, utterly ill-equipped for the age of sovereign AI and quantum computing. Without these enshrined rights, citizens are not participants in this revolution; they are the raw material, their health records and digital footprints the currency in a deal struck far above their heads.

What is perhaps most revealing is the blurring of lines between the state and the boardroom. The government’s own press release celebrating the deal reads like a corporate shareholder report, quoting the CEOs of NVIDIA, OpenAI, and Microsoft at length. Their voices are not presented as external partners but as integral players in a shared national project. When Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, declares that “Stargate UK builds on this foundation,” it raises the fundamental question: who is building what, and for whom?

This unprecedented integration of Big Tech into the fabric of national infrastructure raises profound questions about sovereignty and control. These data centres and supercomputers are not just buildings; they are the “factories of the future,” processing everything from sensitive healthcare data from the UK Biobank to research that will define our national security. By handing the keys to this infrastructure to foreign entities, the UK risks becoming a digital vassal state, reliant on the goodwill and strategic interests of corporations whose primary allegiance is to their shareholders, not to the British public.

The “Tech Prosperity Deal” has been sold as a triumph of post-Brexit, “Global Britain.” But the reality is far more sobering. It is a deal that sees the government leveraging its power to reduce tax income, strain the national grid, and cede control of critical infrastructure, all to entice a handful of the world’s most powerful companies. The handshake may have been for £31 billion, but the price of Britain’s digital independence could prove to be far higher.

Further Reading and Sources

Official Government Announcements and Policies:

- The US-UK Tech Prosperity Deal Announcement (16 September 2025): The full press release from the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology and 10 Downing Street.

- Guidance on UK Freeports: Details on the tax and customs benefits offered within Freeport zones.

- Policy Paper on UK Investment Zones: The government’s framework for Investment Zones and associated incentives.

Digital Rights and Privacy Advocacy:

- Open Rights Group: A leading UK organisation campaigning for digital rights and privacy, with analysis on AI and data protection.

- Big Brother Watch: Investigates and challenges threats to civil liberties, including state surveillance and the use of private data.

Data and Infrastructure Context:

- UK Biobank – Data Access and Governance: Information on how the UK Biobank protects participant data while enabling research.

- National Grid – Future Energy Scenarios: Reports on the future demands and challenges facing the UK’s energy infrastructure.

I understand your concerns about the recent deal between the UK government and Big Tech, especially regarding data privacy and national security. It’s a complex issue with various potential implications.

On one hand, proponents of the deal might argue that collaborations with leading technology companies can bring significant benefits, such as:

- Economic Growth: Attracting investment and creating jobs in the tech sector.

- Technological Advancement: Gaining access to cutting-edge research, development, and infrastructure that could boost the UK’s scientific and technological capabilities.

- Improved Public Services: Utilizing advanced data analytics and cloud computing to enhance efficiency and effectiveness in areas like healthcare (e.g., accelerating medical research through projects like the UK Biobank) and national security.

- Global Competitiveness: Ensuring the UK remains a key player in the global digital economy.

Concerns about data sovereignty and the potential risks are valid. Here are some of the “what ifs” that often arise in discussions like this:

- Data Security and Privacy:

- Breaches: The risk of data breaches increases when sensitive information is stored and processed by third-party corporations, regardless of their size or security measures.

- Jurisdiction: In cases of international corporations, questions arise about which country’s laws apply to data privacy and protection, potentially complicating legal recourse for UK citizens.

- Usage of Data: Concerns about how this data might be used beyond the stated purpose, including for commercial gain or even by foreign governments, especially if those corporations are subject to laws in their home countries that compel data access.

- National Security Implications:

- Foreign Influence: The potential for foreign governments to gain indirect access to sensitive national security research or infrastructure through these corporations.

- Critical Infrastructure: If essential services become overly reliant on foreign-owned tech infrastructure, it could pose a risk during international disputes or cyber-attacks.

- Loss of Control and Sovereignty:

- Policy Influence: Big Tech companies wield significant influence, and collaborations could lead to their greater sway over UK policy and regulatory frameworks.

- Dependence: Becoming overly dependent on specific foreign providers could limit the UK’s long-term strategic autonomy in the digital sphere.

- Ethical Considerations:

- Bias in Algorithms: If AI and data analytics tools provided by these companies are used in public services, there’s a risk of embedded biases affecting outcomes for citizens.

- Transparency: The level of transparency around how data is managed, accessed, and secured by these corporations can be a major point of contention.

These are all important points for public discussion and robust oversight. Governments typically try to mitigate these risks through strict contractual agreements, data protection regulations (like GDPR in the UK), independent audits, and national security assessments. The effectiveness of these safeguards is often the subject of ongoing debate and scrutiny.