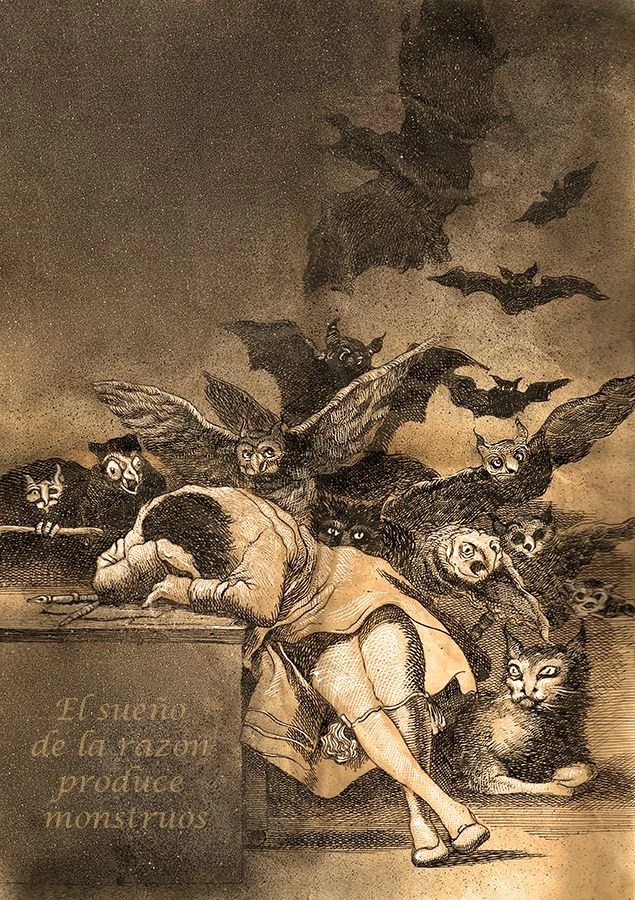

In Francisco Goya’s 1799 etching, The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, the artist is not merely napping. He has collapsed. His tools, the pens and paper of the Enlightenment, lie abandoned on the desk. Behind him, a swarm of owls and bats emerges from the blackness.

Goya’s Los Caprichos served as a warning to Spanish society, blinded by superstition and corruption. But today, the etching feels like a live-stream of the 2026 news cycle.

When reason sleeps, we don’t just dream of monsters. We build them.

The New Bestiary: Algorithms and Echoes

In the post-truth era, the “monsters” are digital. They are the algorithms that prioritise cortisol over comprehension.

According to the 2025 Digital News Report, we have reached a tipping point: 47% of the global population now identifies national politicians and “influencers” as the primary architects of disinformation. Reason hasn’t just faltered; it has been outsourced to partisan actors who benefit from its absence.

The Arendtian Nightmare

The political philosopher Hannah Arendt understood that the goal of total deception is not to make people believe a lie. It is intended to ensure that they can no longer distinguish between truth and falsehood.

In her 1967 essay Truth and Politics, Arendt warned that factual truth is “manoeuvred out of the world” by those in power. We see this today in the “defactualisation” of our economy. Despite rising consumer prices and growing unemployment, a barrage of “official” narratives in 2025 and 2026 has attempted to frame the economy as flawless. As Arendt predicted, when the public is subjected to constant, conflicting falsehoods, they don’t become informed—they become cynical and paralysed.

The Outrage Addiction

Why do we let the monsters in? Because they feel good.

Neuroscience tells us that outrage is a biological reward. A landmark study by Dominique de Quervain showed that the act of “punishing” a perceived villain lights up the dorsal striatum—the brain’s pleasure centre.

Social media is essentially a delivery system for this chemical hit. We are trapped in a cycle in which we conflate “online fury” with “social change.” This outrage functions as a smokescreen: while we argue over individual “villains” on our feeds, the structural monsters: inequality, surveillance, and capture – continue their work undisturbed.

The Architecture of the 1%

While the public is distracted by the digital swarm, wealth has been consolidated into a fortress. In 2026, the global wealth gap is no longer a gap; it is a chasm.

- The Fortune: Billionaire wealth hit $18.3 trillion this year, an 81% increase since 2020.

- The Control: The top 1% now own 37% of global assets, holding eighteen times the wealth of the bottom 50% combined.

This concentration of capital is the ultimate “monster.” It allows a tiny elite—who are 4,000 times more likely to hold political office than the average person—to dictate the boundaries of reality.

Cognitive Atrophy: The AI Trap

Our most vital tool for resistance, the human mind, is being blunted. A 2025 MIT study confirmed that heavy reliance on Large Language Models (LLMs) for critical thinking tasks correlates with weakened neural connectivity and a “doom loop” of cognitive dependency.

As the Brookings Institution warned in early 2026, we are witnessing a “cognitive atrophy.” If we offload our judgment to machines owned by the 1%, we lose the very faculty required to recognise the monsters in the first place.

Case Study: The Epstein Files and Systemic Silence

The release of 3 million pages of Epstein documents in January 2026 should have been a moment of total reckoning. With 300 “politically exposed persons” implicated—from British peers to European heads of state, the scale of the rot is undeniable.

Yet, the reaction has been a repeat of Goya’s etching. We focus on the “monsters” (the names in the files) while ignoring the “sleep” (the legal impunity and wealth-purchased silence) that enabled their existence. Epstein was not a glitch in the system; he was a feature of it.

Waking the Artist

Goya’s etching ends with a caption: “Imagination abandoned by reason produces impossible monsters; united with her, she is the mother of the arts and the source of their wonders.”

To wake up in 2026 requires more than “fact-checking.” It requires a reclamation of our tools:

- Cognitive Sovereignty: Limit the AI-driven “doom loop” and reclaim the capacity for independent analysis.

- Structural Sight: Stop chasing the “bats and owls” of individual outrage and look at the “desk”—the economic and political structures that house them.

- Institutional Integrity: Support the few remaining impartial bodies capable of holding power to account.

The monsters only vanish when the artist wakes up. It is time to pick up the tools.

Key References

- Reuters Institute: Digital News Report 2025

- Hannah Arendt: Truth and Politics (Yale Edition)

- Oxfam International: The 2025 Wealth Gap Report

- MIT Media Lab: Cognitive Debt in the Age of AI

- U.S. Department of Justice: January 2026 Epstein File Release Summary